Displaced Villagers of Bokaro Steel Plant Burn in Furnace of Apathy

Displaced youths protesting at a gate of Bokaro Steel Plant.

In the third week of July, around 700 youths staged a protest at the gate of Bokaro Steel Plant, Jharkhand. Assembled under the banner of Displaced Apprentices Association, a union of the villagers displaced by the construction of Bokaro Steel Plant, the protesters locked its main gate in an act of defiance.

The sit-in protest, which started on 13 July, ended on 18 July when representatives of Steel Authority of India Limited (SAIL) met the youths and assured them of considering their demands within 15 days.

The plant, built with Soviet assistance in 1965, was India’s fourth integrated public sector steel plant and managed by Bokaro Steel Limited (BSL), which was established in 1964. In 1978, the BSL was merged with SAIL in accordance with the Public Sector Iron and Steel Companies Restructuring and Miscellaneous Provision Act.

A shot of the Bokaro Steel Plant.

When the plant was proposed in 1956, the-then Shri Krishna Sinha-led Bihar government swiftly approved the proposal and provided 31,287.24 acres, including 26,908.565 acres of the acquired land, 3,600.215 acres of gair majarua, which was free of cost, and 778.46 acres of forest land.

Within days, the state government vacated the land and handed it to Bokaro Steel Plant, but due to lack of agreement on proper rehabilitation and planning, 20 mauzas (which include several groups of villages) of 825.855 acres could not be vacated. While SAIL claims these 20 mauzas, the villages claim it as their acquired land, whose rehabilitation is pending for the last six decades.

“Our families can’t avail government schemes. Even during the first Covid wave, when the government was assisting the general population, we didn’t get any help,” said Rajesh Turi, a native of Chetatand, one of the affected villages. The villagers, who call themselves visthapit (displaced) and lawaris (unclaimed), have formed an organisation called Jharkhand Visthapit Samaj.

Residents of Mahuaar Mauza share their ordeal.

Why do villagers call themselves lawaris

Situated in Bokaro Steel City, the area is surrounded by several industries, including Bokaro Thermal Power Plant, Chandrapura Power Plant and Chandankiyari Township. Since the villages are located on the disputed land, 19 of the 20 mauzas tare devoid of any panchayat.

Though a majority of the around 70,000 villagers inhabiting these 19 mauzas are part of the electoral roll, they are not entitled to rural schemes due to lack of official recognition.

The villagers were not hired a labourers even during the height of unemployment as the pandemic peaked. Jharilal Mahto, a native of Shibutand village, said that SAIL is building roads and a GAIL plant is also being set up here. “We also got to know of plans to construct a stadium. But these companies don’t hire us as labourers fearing it might lead to our official recognition.” Unemployment has spiked with villagers cycling to the city for work, he added.

Darkness under the disguise of development

Even the few villagers hired as contractual workers or labourers by SAIL allege that they are paid less than the agreed amount due to corrupt contractors and officials. “A large part of our wages is kept by the contractors, who threaten us if we protest. Many senior officers of SAIL are being investigated for corruption,” said Virendra Kumar, a contractual worker in SAIL and spokesperson of the Bokaro unit of All India Trade Union Congress.

Another villager Kunwar Rajan Singh said, “Our ancestors were promised development, employment, good education and health care facilities while the plant was being established. Soon, it turned into a nightmare. My ancestors sold their land to the government at very cheap rates. But neither the government nor the SAIL administration kept the promises.”

The once-fertile land has turned barren after being buried by factory waste.

The villagers face police action if they try to construct anything on their land as it was officially acquired. “Our land has turned barren due to pollution caused by the plant. Agriculture, our primary source of livelihood, is not possible anymore. Even the streams of the Damodar River, which was the source of our drinking water, are now contaminated,” said local activist Binod Rai.

Once a source of drinkable water, the stream, which joins the Damodar River a few kilometres further, has now turned into a drain.

It has been more than one month since SAIL assured the protesting youths of considering their demands within 15 days. The villagers are again losing hope. “We have conveyed our suffering to the district administration, MPs, MLAs and the chief minister, but all of them have disappointed us. We are left with no other option but to agitate on roads because all the governments in the past five decades have disappointed us,” said Arvind Kumar, a member of the Jharkhand Krantikari Mazdoor Union and Visthapit Sajha Manch.

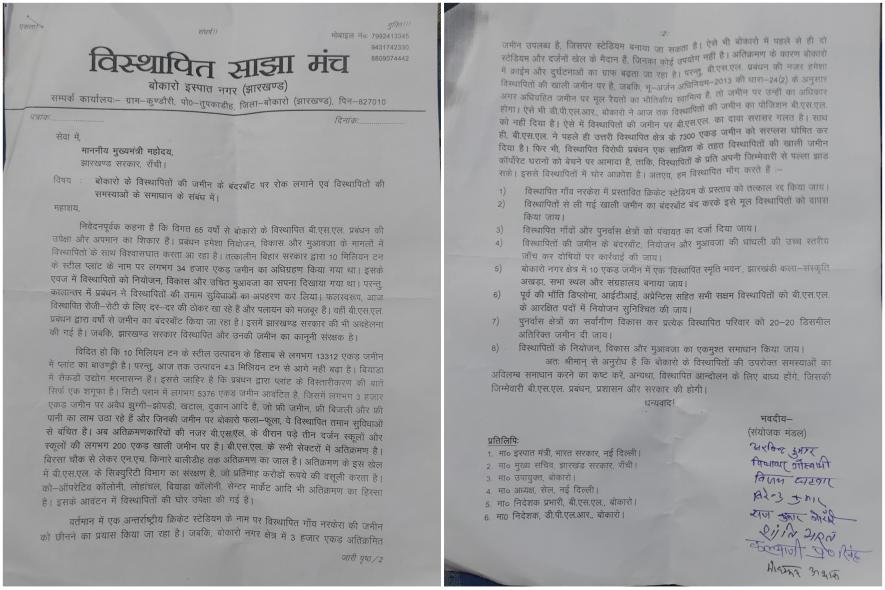

The letter sent to Jharkhand CM Hemant Soren by the displaced residents.

Vikram Raj is an independent journalist and a student of University of Delhi. The views expressed are personal

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.