Will Lynching in Bharat Be Called Vaddh?

The speech by Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) supremo Mohan Bhagwat on its foundation day (Dusshera) has now become an event, watched with interest. The speech itself has a long tradition within the organisation, which all its affiliated (anushangik) bodies look upon as a guiding light.

This year was no different. Donning the Sangh’s uniform, the top echelons of its organisations attended the event. Union Minister Nitin Gadkari, Maharashtra Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis attended too, and wore the black cap and Sangh “uniform”.

Yet, the speech by Bhagwat itself had nothing seemingly strategic. Some analysts even felt that he could not show any new direction to the RSS and its affiliates; that it seemed to have made a weak defence of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government that is ruling at the Centre and several states. “Have the tables turned on the Sangh Parivar?,’ The Wire asked, in its analysis of Bhagwat’s speech.

Bhagwat exhibited a rather weak understanding of economics and the ongoing slowdown in India when he said that there is “no need to discuss the slowdown” because that would “further aggravate it”. He also said that a “recession” means a growth rate of “less than zero”. (Generally, economists define a recession as six months or more of negative economic growth.) Bhagwat did not care to dwell on the mismanagement of the economy by the BJP-led government. Nor did he talk about government taking steps to control the malaise of lynching that is pulsing through the country since the last five years.

The ascent of majoritarian forces in India’s polity and society in the second decade of the 21st Century is related to these sudden eruptions of lynching events. One of the earliest cases of lynching in this wave of murders took place less than a fortnight after the swearing-in of the first government led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in May 2014.

On June 4, 2014, Mohsin Mohammed Shaikh, a 28-year-old information technology manager in Pune, was lynched by a group said to be associated with a Right-wing outfit, the Hindu Rashtra Sena. The murder had disastrous consequences for Shaikh, his family, and society, for, ever since then, the phenomenon of innocents being “put to death by mob action without legal approval or permission” never stopped.

One feature of targeted violence is that it is not the act of one individual against another—one person thrashing another or even killing another, for example. Targeted attacks the form of group violence. These mobs in India have been targeting religious minorities, dalits, transgender persons, women and other deprived and weaker sections.

Anyone considered the ‘other’ is fair game in India. Noted social scientist, Sanjay Subrahmanyam, who teaches at the University of California Los Angeles, has said that the members of lynch mobs know that their acts have the approval of higher authorities. This is what gives them the confidence to carry on their heinous crime without fear.

Forget the critics, even the admirers and supporters of the present dispensation feel that lynching is one issue that has got the Narendra Modi government a lot of bad press. On one occasion in 2016, even Modi had to condemn vigilantism (though he has since prevaricated on the issue). The condemnation also came about only when there was a massive uproar over cow-protection mobs flogging Dalits in Una, Gujarat, and other attacks against Dalits and minorities in different parts of the country.

As there has been no let-up in gruesome lynching, it was only natural that the Sangh supremo was expect to (at least formally) say that such killings are unacceptable. Of course, he could then have sung paeans to the tolerance of Hindu religion and criticise the government for not doing enough. But what happened was exactly the opposite.

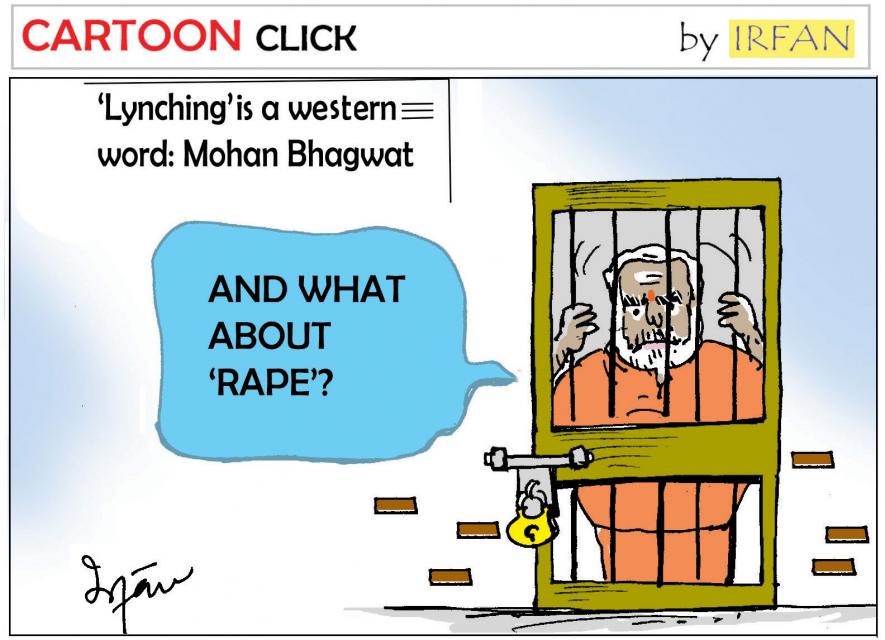

Bhagwat tried to spin the whole issue by saying that the very concept of lynching is “alien to Bharat”. He traced the genesis of murderous mobs to the Bible, the holy book of Christians, who are a minority in India. According to him, lynching was being used to defame the “country and the entire Hindu society”. Instead of seeing it as a mob action on an individual without legal approval, which is what is really happening, he attempted to paint lynching as a fight between two communities.

As expected, there was a strong reaction from Opposition leaders over Bhagwat’s tremendous concern for vocabulary but not over the heinous incidents of lynching. He was also admonished for turning a blind eye to the glorification of the accused by cabinet ministers. Many BJP leaders have garlanded those accused of lynching. The body of at least one such accused was draped in the Tricolour at a ceremony that a minister attended.

Anyone who has closely watched the saffron, knows that bringing up the vocabulary was not an inadvertent error. Playing with words, raising issues of semantics is their time-tested method. It reflects their cunning that all their acts based on the ideas of hate and exclusion are cloaked in sanitised words: Cow vigilantes are called cow protectors, those who demolished the Babri mosque were called “Kar Sevak” and the Gujarat riots were justified as “action-reaction”

Think of how the phrase “collateral damage”, which supposedly originated from the Vietnam War, gained wide currency during the 1991 United States’ attack on Iraq. This phrase papers over the killing of civilians during attacks on other targets. As a euphemism, it insulates the one doing the killing from any feelings of revulsion or moral outrage.

The Hindutva supremacists of the Sangh, like fellow-fanatics who claim allegiance to other religions, have always used words carefully, sanitising their crimes against humanity to protect themselves. For example, consider their description of the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, whose ideas of Hinduism are at complete variance with Hindutva.

In Maharashtra, where this heinous ideology was incubated for decades, and from where its leading ideologues and executioners came, a conspiracy was hatched by VD Savarkar and his group of fanatics (Kapoor Commission). They, in popular parlance, described Gandhi’s cold-blooded murder as “Gandhi vaddh”.

A scholar of Sanskrit language and literature would say that “vaddh” means nothing but murder, but supposedly one done in pursuit of a noble cause. Thus, the killing of Kansa by Krishna is called “Kansa vaddh”. Or, the killing of Shambuka in the Hindu epic, Ramayana—who is a shudra scholar—is also referred to as “Shambuka vaddh”. Perhaps, it would be opportune here to look at Ramayana itself, where ‘vaddh’ is referred to many-a-times.

The killing of Shambuka appears in the Valmiki Ramayana, Book 7, the “Uttarakanda”, or final chapter, in the sargas 73 to 76.

73: When Rama is reigning as a virtuous king, a humble aged brahmin comes to him, weeping, with his dead son in his arms. He says that Rama must have committed some sin, or else his son would not have died.

74: The sage Narada explains to Rama that a shudra is practicing penances, and this is the cause of the child’s death.

75: Rama goes on an inspection tour on his flying chariot and finds an ascetic doing austerities, and asks who he is.

76. “...he was yet speaking [when] Raghava [Rama], drawing his brilliant and stainless sword from its scabbard, cut off his head. The shudra being slain, all the gods and their leaders with Agni’s followers cried out, “Well done! Well done!” overwhelming Rama with praise, and a rain of celestial flowers of divine fragrance fell on all sides, scattered by Vayu.” (583-84)

(The Ramayana of Valmiki translated by Hari Prasad Shastri, London: Shanti Sadan, 1970.)

For the Hindutva supremacists, Gandhi was the biggest obstacle—the “demon who needed to be exterminated”, as a caption to a 1945 cartoon in a Hindutva weekly said. This cartoon portrayed Gandhi as a Ravana with 10 heads that Hindu Rashtra proponents were taking aim at. Thus, it is not a surprise that with their deep influence over articulate sections of Maharashtrian society—a majority of whom were brahmins at the time—it was rather easy for them to popularise this planned killing as a justified “vaddh”.

Bhagwat, perhaps should have dwelled upon this aspect of vocabulary, while he was at it: whether lynching could be replaced, according to him, by “vaddh” a very indigenous concept that has been practised from time immemorial.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.